When author Dani Shapiro took a DNA test at age 54, she discovered that the man who’d raised her wasn’t her father. Her 2019 book Inheritance: A Memoir of Genealogy, Paternity, and Love, details her search for answers surrounding her conception and her painful and miraculous journey toward gaining a truer expression of her identity. I have long been fascinated by the stories our genes tell us, even when we don’t have a code-breaker translating their messages from the past to us.

Shapiro reflected on the clues embedded in her own writing:

I had reread some of my early books in recent weeks and was taken aback, again and again, at the choice I’d made, the language I’d used – particularly in my fiction – that pointed to some sort of consciousness lurking just beyond my ability to perceive it. The truth had been inside me all along.

In my first, highly autobiographical novel, the narrator is aware that she is out of place in her father’s Orthodox Jewish family and longs to be a part of them. But she is haunted by the fact that no one ever recognizes her as part of the family by her face. In a much later novel, a secret wears away at a family until it is very nearly destroyed, parents with the best of intentions make selfish decisions affecting the fate of their child. What had I known without knowing?

I grew up knowing the outline of my mother’s story: Her mother, my maternal grandmother Molly Klopman, died shortly after giving birth to her in 1938 in New York City. Her father, George, wasn’t able to care for a newborn. An infertile cousin and her husband in Chicago agreed to adopt the baby with the proviso that the adoption remain a secret. Everyone in the family agreed it would be for the best. But shortly before my mother was to marry, George called and spilled the truth in 1957. He wanted to come to the wedding to see Molly’s baby walk down the aisle.

That explosion blew up my mom’s life, though no one really understood precisely how deep the damage was at the time. Instead, the shrapnel was reconfigured in time for happy family pictures with the parents who’d raised her. I’ve been told George came to the wedding and sat in the back of the room. He’s not in any of the pictures in the wedding album.

Though we didn’t talk about it much, that secret shaped my family’s experience in ways I’m still discovering. But it wasn’t until I read Shapiro’s words about her own early writing that I realized that Molly had been talking to me even when I didn’t know how to translate what she’d been saying.

When I first started writing as an adult during the 1980’s and 1990’s, I focused almost entirely on playwriting. When the opportunity was presented to me to try my hand writing some radio scripts, then to put together a play that senior citizens could perform, I gave myself an immersion course in scriptwriting by cleaning out the shelves on the topic at my local library, reading plays, and eavesdropping on conversations to study the rhythms of speech. And then wonder of wonder, miracle of miracles, things that I wrote made it to the radio and to the stage.

No one in my immediate family had the slightest inclination toward theater. I’d never been in a school play. Though I’d always loved to write, there was no logical reason that I should have been drawn to playwriting. It wasn’t until I read Shapiro’s words that I understood what the scripts I was writing were telling me.

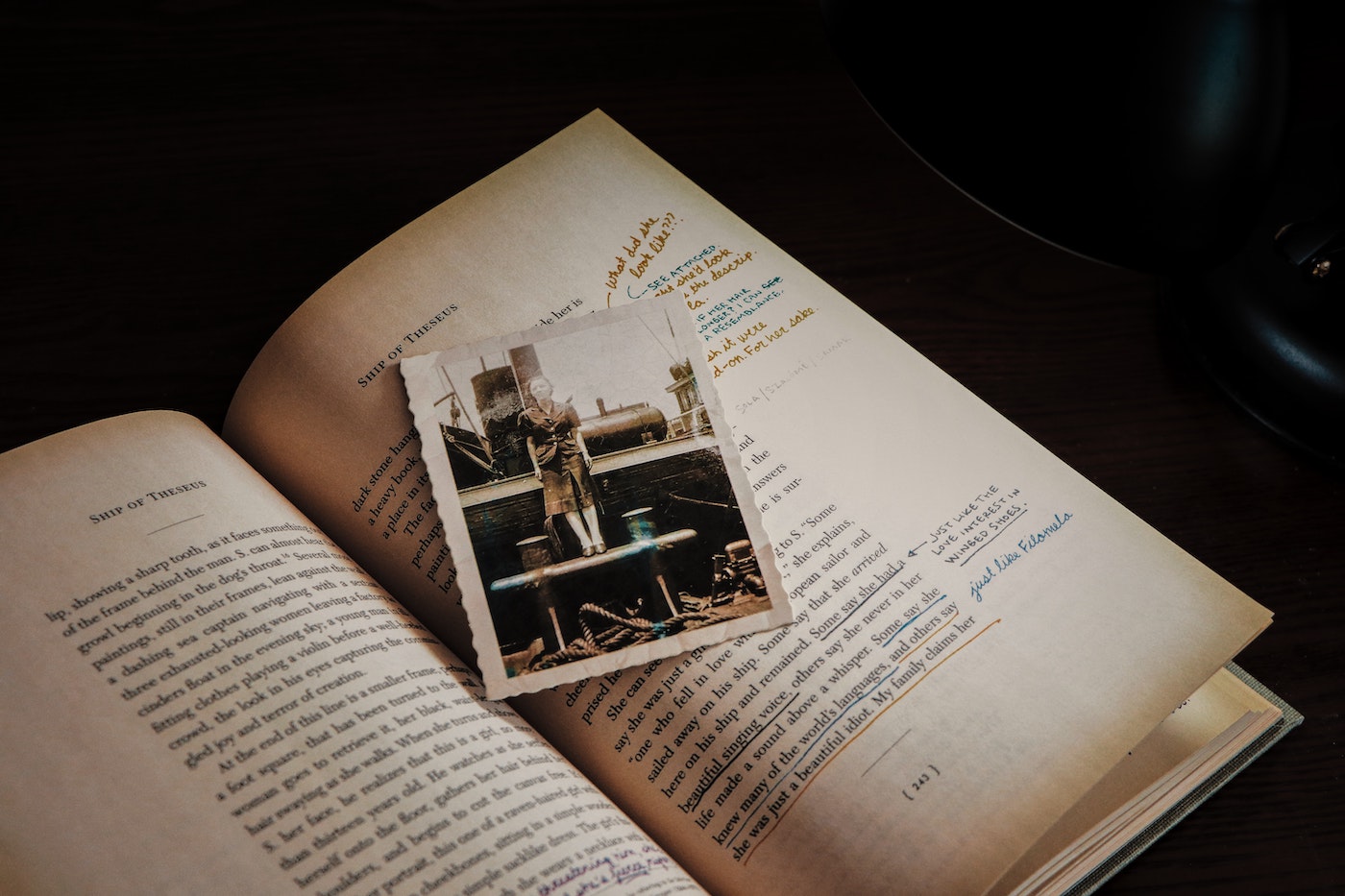

After my mom died in 2007, a cousin sent me some pictures of Molly and George Klopman. Only then I learned that Molly Klopman was active in Yiddish theater in Poland before she came to the U.S. in 1920. She is third from the left in the cast picture above, acting in the play Mirele Efros.

What had I known without knowing?

Some may mark this merely as a coincidence. But I suspect that just as eye color or lactose intolerance gets transmitted through DNA, so do other things that can’t be measured or quantified. Like how to tell a story in 3-D.

The lines have fallen to me in pleasant places; Indeed, my heritage is beautiful to me. (Ps. 16:6)

We bear pain in our lives, the result of generational trauma. We transmit some kinds of disease via errant genes. But there are also gifts of our heritage, clues buried below the surface of our conscious experience, like a love letter in a time capsule.

How about you? Have you discovered some surprising connection between your life and the life of a relative from an earlier generation?

Cover photo by Jason Wong on Unsplash

Love this! Maybe when I take flowers to the cemetery on Monday I’ll linger a while and think about the lives of my great grandparents . You will be able to visualize me there.

Yes, I will. Miss you!

That is so cool! I wasn’t at all surprised about the alcoholism because it’s well known on my mom’s side of the family. But I did learn something from my dad’s side. I can sort of see the future. I say sort of because I’ve never gotten a specific revelation of what’s going to happen, but I get a sense that either something is going to happen or that I need to do something immediately. For instance, when I was 11 or 12 years old, I was swinging on a rope swing in the back yard. I would swing as high as I could and then jump out of it as it peaked before the back swing. That one day just as I got the the peak of the back swing before going forward I had this thought that I needed to stop as soon as I could touch the ground. As soon as I planted my feet on the ground, the rope broke on one side. Last year I was getting all my genealogy papers together merging what my mom had into mine when I found a questionaire my dad’s youngest sister had filled out for another cousin and gave me a copy. She had written a short narrative of what she remembered about her maternal grandfather, and in that she said that he described airplanes prior to their invention. Since then I’ve wondered if my “gifting” has a genetic aspect. Also, he was a preacher, and several uncles and an 8th great grandfather were preachers so that might be where my desire to preach comes from. 🙂

Thank you for sharing! I love your story!

There is definitely a spiritual aspect to our DNA, isn’t there? It’s remarkable to put some of the seemingly-random pieces of our existence together like you have.

After reading this, my heart says, “Oh, how I’d love to meet Molly!!” then I think: WAIT – I just did. In this post.

Oh, how I’d like to get to know her better . . . . but WAIT – I am getting to know her better and better, because I read and ponder her granddaughter’s writing.

That picture of your grandmother is stunning. It’s like looking into a deep well. Thanks for sharing this!!